C

How we can ensure that patients consistently receive appropriate and expert care, from the community to the hospital

Mhairi Collie, Graham Mackay, Jon Randall, Arun Sahai, Nikesh Thiruchelvam, Charles Knowles (editor)

Across the UK, patients are presented with an inequality of access to care resulting from the patchy nature of services for continence and functional pelvic conditions. Expertise in assessment and management of pelvic floor disorders is unevenly distributed around the country, presenting challenges for both clinicians and patients in navigating the pathways of care. Further, community continence care is facing funding and manpower shortages in some regions.

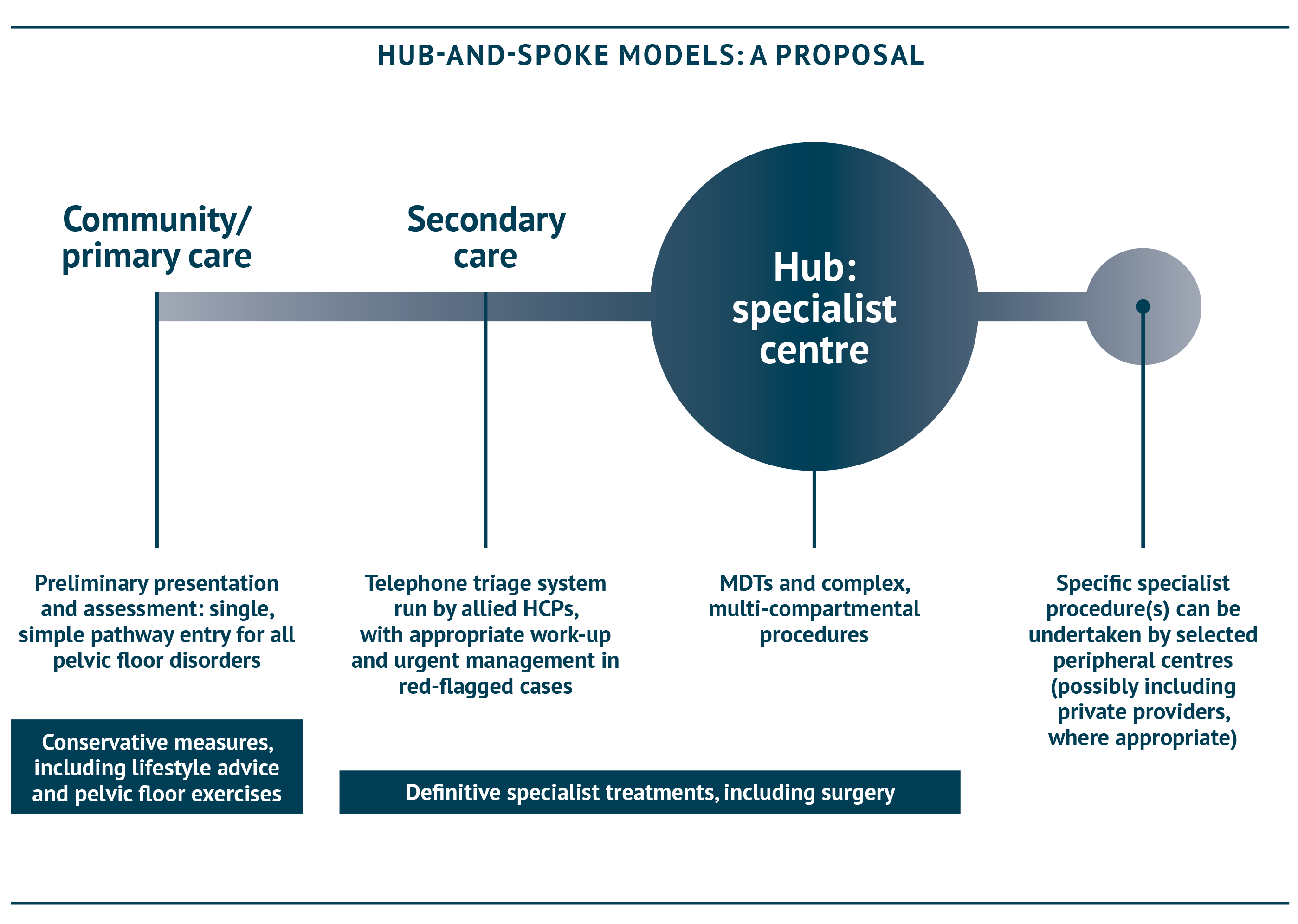

Improved support for community care is essential: community-based continence promotion and care services have been shown to improve outcomes for children and adults, as well as reducing the need for incontinence products, hospital and social care and associated costs (APPG for Bladder and Bowel Continence Care, 2011; Tannenbaum et al., 2019; Stephenson, 2019). In addition, implementation of a hub-and-spoke model – with a multidisciplinary team (MDT) at the centre – would help to provide equity of care for patients, no matter their location in the UK. Integrated Care Systems, bringing together local healthcare organisations to create coordinated care plans for the local population, are a key part of the NHS Long-Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) and this model would align closely with that ambition.

“In the future,] greater access to and sharing of data, widespread availability of new technologies and remote support of experts may reduce inequalities and variation in treatment outcomes between different hospitals”

Royal College of Surgeons, 2018. Future of Surgery

The variable nature of continence care provision in the UK is reflected across settings. In some areas, community continence services have a low level of service provision or have even been forced to shut temporarily, owing to a lack of funding and a high workload. Additionally, specialist continence nurses and other allied health professionals, trained in continence and pelvic health, who have a key role in assessment and treatment (as identified by the NHS England Excellence in Continence Care report in 2018 [NHS England, Excellence in Continence Care, 2018]), are not available to all hospitals, and a large number of community continence advisors are approaching retirement, potentially leading to a sharp drop in available workforce. There are clear disparities in the provision of paediatric bladder and bowel services (Paediatric Continence Forum, 2017).

Referral and self-referral from primary care to community continence services – where those services exist – is often straightforward. However, referral onwards to secondary care can be problematic: which patients should be referred, to where, and by whom? Assessment and treatment in secondary care is often perfunctory with attention focussed on exclusion of cancer rather than addressing patients’ primary complaints, as the primary focus becomes achieving cancer exclusion targets. Such patients may or may not be referred on to other secondary specialists with an interest in pelvic disorders, or to tertiary care. In addition, progress through these steps may take years.

KEY POINTS

- Community continence care is essential and must be adequately funded for all ages, including children and young people; triaging patients ahead of hospital referral can also help to ensure those whose condition is able to be managed in the community or primary care are identified and directed to appropriate support

- A hub-and-spoke approach could not only allow regions to make the most of local expertise and capacity, but also provide opportunities for training the workforce of the future

- Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) are critical to ensure patients receive specialist care, but must reach an appropriate standard, as recommended by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Continence Care; accreditation from the Pelvic Floor Society is available and has been embraced by a number of hospitals in England already

Supporting community and primary care

Community continence care is a critical base for the service and must be adequately funded. The majority of patients can be managed with non-surgical measures and adequate pre-hospital care can reduce the need for surgery and for complications necessitating admission, such as sepsis from urinary tract infections. In Leicester, an estimated 80% of patients with vaginal prolapse and urinary problems reported improvement with conservative management alone, with high success rates (see case study). Making sure that community continence services are adequately resourced and are able to efficiently triage patients will ensure that the right patients are referred to the right services, should their needs be more complex. A national minimum standard of care and of staffing has previously been recommended for continence care in the community and beyond (APPG for Bladder and Bowel Continence Care, 2011; NHS England, Excellence in Continence Care, 2018), and would help to ensure consistency of services for patients around the country.

When patients enter the system in the primary care setting, they are assigned a code relating to their identified disorder. At present, despite the frequency of overlapping pelvic floor disorders, each code refers to a separate compartment. Ideally, assigning a single code to all pelvic floor disorders would provide a single point of entry for pelvic floor patients, simplifying the pathway and improving the patient’s experience.

REDUCING THE LOAD ON HOSPITALS: TELEPHONE TRIAGE

At St Mark’s and Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals in London, patients undergo telephone triage assessment by allied healthcare professionals and are screened for problems potentially requiring specialist management: a large proportion can be managed with advice and conservative measures, allowing specialists to focus on the more complex cases.

Hub-and-spoke models

A hub-and-spoke approach is already the direction of travel for healthcare, and could allow regions to make the most of existing expertise and capacity. Specialist expertise, capacity or facilities may be available in the spokes, not just the hubs, so it is essential that the right hub/spoke model is set up based on the circumstances of a particular region.

MDTs (see diagram on next page) are a key enabler to make this hub and spoke model work. These can take place largely in the ‘hubs’, with remote meeting technology allowing experts in the spokes to join the meetings easily and efficiently.

Devolving some expert procedures to smaller units would allow larger specialist centres to focus on highly specialist work, potentially resulting in fewer complications and better outcomes. It may be that some services could be provided by private hospitals or independent treatment centres if local needs require it and adequate integration can be achieved with the NHS MDT. In the oncology field, national-level implementation ensured such a change in approach happened quickly and effectively (NHS England, Implementing a timed colorectal cancer pathway, 2018): this would also be welcomed in the continence and pelvic health field. However, while national-level guidance is awaited, MDT working at a regional level should be implemented to support better outcomes for patients as swiftly as possible.

The provision of adequate training is essential to safeguard the future of pelvic floor medicine, to maintain standards and to ensure outcomes for patients continue to improve (see Chapter D). Implementing a hub-and-spoke structure could also help to ensure provision of training opportunities. At present, most trainees struggle to meet the required number of procedures to qualify in their chosen specialty, for example for prolapse repair: with cases concentrated in dedicated centres, trainees can be offered the opportunity to participate on a more frequent basis.

Where some procedures become increasingly specialised, consideration must also be given to emergency procedures, such as emergency presentation of irreducible prolapse. A plan should be agreed within regional and local teams to define referral pathways and ensure support is available in these cases.

THE SITUATION IN SCOTLAND

In Scotland, there are separate services for sacral neuromodulation (SNM) for bowel and urinary incontinence. The bowel service is a managed clinical network, with centres including Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Dundee and Inverness offering this service. For urinary incontinence, a Scottish National Service was set up in 2010 but de-designated in 2019 in order to set up 3 regional services; unfortunately, this has led to patchy, unequal service.

In the community setting, there were well-developed services in the West of Scotland for urinary incontinence but limited experience of bowel incontinence until recently: work has been ongoing in the past few years to redress the balance and ensure equity of care.

Multi-disciplinary decision making

Developing multispecialty services for pelvic floor procedures is expected to improve outcomes, as well as access, compared with the current approach where procedures are conducted within the individual specialties of coloproctology, gynaecology and urology. Commissioning (in England) is a key step to ensure that defined pathways exist for treatment. A clear map of the location and provision of available services will be important to develop an algorithm to support appropriate referrals in future; a planned initiative to map out available continence services under NHS England is currently on hold as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, but must not be forgotten.

MDT-based decision making is critical for optimal care for patients’ often complex disorders – but it is not yet a universal approach. A survey of colorectal surgeons in 2014 found approximately 50% of respondents used pelvic floor MDT meetings (Beggs et al., 2014). A census of 67 centres in the same year found that 38 (57%) held regular MDT meetings, although only a third did so in conjunction with another unit (ACPGBI PF census report, 2014).

Further, MDTs must reach an appropriate standard in order to be effective. The British Society of Urogynaecology has led accreditation of units specialising in urogynaecology for over 10 years. The Pelvic Floor Society now also offers voluntary accreditation to units with MDTs that meet appropriate criteria, including appropriate attendance and infrastructure and ensuring that mechanisms are in place to identify which patients should be discussed (The Pelvic Floor Society). So far, eight units have been formally accredited in the UK, and a further 35 are accredited by the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG). The Pelvic Floor Society is keen to see others sign up to ensure MDT discussion – and thus patient care – are standardised across the country. Learned societies such as the Pelvic Floor Society would support the role of commissioning in driving mandatory accreditation to maintain and improve quality. An achievable and laudable target would be to double the number of accredited centres in the next 12 months.

ACCREDITED UNITS IN THE UK

The following units have received MDT accreditation from the Pelvic Floor Society at the time of writing:

- Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust, London

- Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London

- St Mark’s Hospital, London

- Bristol Cross City, North Bristol and University Hospitals Bristol Trusts

- Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

- University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, Plymouth

- Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield Teaching Hospital, Sheffield

- University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

REFERENCES

ACPGBI, 2014. Census of current colorectal practice across the UK. Chapter 9: Resources for Pelvic Floor Services. Available at: https://thepelvicfloorsociety.co.uk/qa-governance/accreditation-of-pelvic-floor-units/ (last accessed January 2021).

All-Party Parliamentary Group for Bladder and Bowel Continence Care, 2011. Cost-effective Commissioning For Continence Care. Available at: http://www.appgcontinence.org.uk/documents/ (last accessed September 2020).

Beggs AD, et al., 2014. The pelvic floor practice of colorectal surgeons and recommendations for future services. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 96:e1–e8.

Elneil S, 2009. Complex pelvic floor failure and associated problems. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 23:555–573.

Gash K, et al., 2015. Training pelvic floor surgeons of the future: Is it time for a change in approach? Bulletin R Coll Surg Engl 97:e10–e14.

National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) Development. Available at: http://www.ncin.org.uk/cancer_type_and_topic_specific_work/multidisciplinary_teams/mdt_development (last accessed September 2020).

NHS England, 2018. Implementing a timed colorectal cancer pathway. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/implementing-timed-colorectal-cancer-diagnostic-pathway.pdf (last accessed September 2020).

NHS England, 2018. Excellence in Continence Care. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/excellence-in-continence-care.pdf (last accessed September 2020).

NHS England, 2019. The NHS Long-Term Plan. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (last accessed September 2020).

Paediatric Continence Forum, 2017. An examination of paediatric continence services across the UK. Available at: http://www.paediatriccontinenceforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/An-examination-of-paediatric-continence-services-across-the-UK-PCF-August-2017.pdf (last accessed April 2021).

Stephenson J, 2019. Nursing Times. Available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/community-news/call-investment-nurse-led-community-continence-services-05-09-2019/ (last accessed November 2020).

Tannenbaum C, et al., 2019. Long-term effect of community-based continence promotion on urinary symptoms, falls and healthy active life expectancy among older women: cluster randomised trial. Age Ageing 48(4):526–532.

The Pelvic Floor Society. Available at: https://thepelvicfloorsociety.co.uk/qa-governance/accreditation-of-pelvic-floor-units/#Accreditation_of_Units (last accessed September 2020).