E

How combining Pelvic Floor expertise can improve the patient experience

Graeme Conn, Chris Harding, Karen Telford, Karen Ward

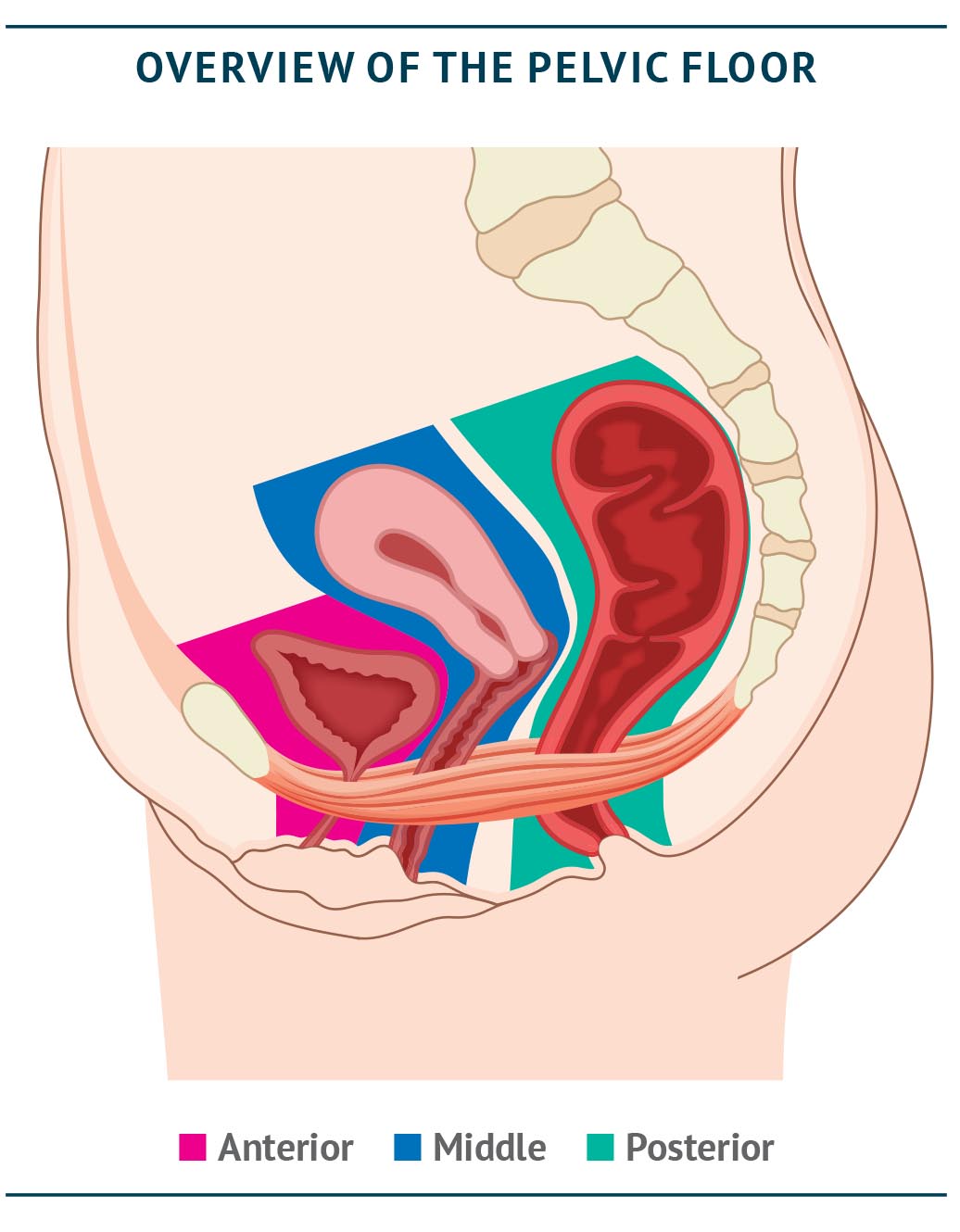

The pelvis is considered to have three compartments: anterior, middle and posterior (Salvador et al., 2019), as shown in the figure below. Historically, different surgical specialties (urology, urogynaecology and colorectal) have tended to ‘colonise’ the pelvis along these lines with each addressing a single compartment. This ignores the basic concept of ‘three compartments – one pelvic floor’ and can lead to repeated patient visits to different specialists and multiple appointments in order to reach the appropriate diagnosis and to initiate consequent treatment (Salvador et al., 2008). Often there is little crossover between these different consultations. This can not only cause frustration for the patient, but also leads to duplication of work for the clinical teams and may delay important procedures. Further, ignorance of multicompartmental problems can lead to lost opportunities to address multiple problems, or even the risk of making the second problem worse, by conducting surgery on one compartment only.

This issue is not trivial. According to a survey of women 20 years after childbirth, around one in three presenting with a pelvic floor disorder (PFD) may in fact have two or more PFDs (Gyhagen et al., 2015). Urology, urogynaecology and colorectal surgeons tend to be highly specialised, but patients with such multifactorial pelvic floor disorders require the input of multiple specialities (Elneil, 2009). Primary care and community continence and pelvic health services do not usually distinguish between the compartments, approaching symptom management in a functional and holistic way. Treating all issues together is an approach that should be adopted for the patient referred to secondary and tertiary care following intial non-surgical management and may allow for efficiencies in an increasingly depleted workforce.

KEY POINTS

- Frequent multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings are recommended, especially to discuss complex, multi-compartmental cases, featuring subspecialist functional colorectal, urology and urogynaecology team members

- Trained nurses and other allied health professionals can conduct selected protocol-driven procedures, freeing up specialist consultants and surgeons to perform other work

- In the future, cross-compartmental training is desirable to ensure joined-up care and to create ‘three-compartment pelvic floor specialists’

Optimising collaboration among pelvic floor specialists: the role of the MDT

Patients with PFDs have already had a difficult journey, often taking years to reach a specialist in secondary or tertiary care. It is of paramount importance that the patient feels looked after in a holistic manner and fragmented care and ‘silos’ should be avoided. Ownership of the problem, with a named responsible clinician in charge of care who liaises with colleagues, can help to avoid patients having to move unnecessarily between specialists.

Joined-up care is particularly essential for our most complex patients, who need a joint evaluation and possibly joint surgery. The optimal approach for these complex cases is the multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting, featuring a range of specialists to ensure the full spectrum of factors is taken into account when deciding on treatment – an approach recommended by the recent Scottish Independent Review into mesh implants (Scottish Independent Review, 2017). Indeed, the MDT is no longer optional and is an essential resource in patient management, and as a minimum standard of care, all patients requiring surgery should be discussed before surgical treatment.

NICE guidelines for urinary incontinence recommend both regional and local MDT meetings (NICE guidelines, Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management, 2019) and state that local MDTs are appropriate to review proposed treatments for patients with primary stress urinary incontinence, overactive bladder or primary prolapse, whereas regional MDTs should review proposed treatments for patients with complex pelvic floor dysfunction and mesh-related problems. Currently, there are approximately 40 commissioned centres for complex pelvic floor problems (focused largely on urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse) to be established under specialised commissioning. In its current iteration, the service specification relates largely to these symptoms and where they coincide with bowel symptoms, rather than for bowel symptoms alone, leaving people presenting with bowel issues alone uncatered for beyond the pelvic health services in primary and community care.

JOINT PELVIC FLOOR MDT – BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST: ‘MOVING IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION’

Multi-disciplinary team meetings (MDMs) were started in 2015 with the remit of discussing all colorectal patients under consideration for pelvic floor surgery and Barts was one of the first two centres to achieve accreditation by the Pelvic Floor Society in 2018. The meeting started monthly, then moved to every 2 weeks and is now weekly, discussing 5–10 patients per meeting. The original membership of urogynaecology, colorectal surgery, nursing, clinical physiology (inc. radiology) has expanded to include monthly attendance of urology and neurogastroenterology as well as physiotherapy, research fellows and nurses (for trial recruitment). In addition, the MDM has become regional with the addition of the Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Hackney, London) and Broomfield Hospital Chelmsford.

NICE recommends that local MDTs should feature as a minimum two consultants with expertise in managing urinary incontinence in women and/or pelvic organ prolapse, a urogynaecology, urology or continence specialist nurse and an accredited (POGP, 2020) pelvic floor specialist physiotherapist. Additional optional members listed in the guidelines are a member of the care of the elderly team, an occupational therapist and a colorectal surgeon. However, for regional MDT meetings, the colorectal surgeon is listed as a mandatory attendee, along with a pelvic floor specialist physiotherapist and a radiologist with expertise in pelvic floor imaging. Notably, the older (2007) guidelines for faecal incontinence do not yet include a recommendation for an MDT (NICE guidelines, Faecal incontinence in adults: management, 2007); given the evidence used for these guidelines is still current, the expected timeline for updating these is not yet known, although there is a guideline in progress from the European Society of Coloproctology (ESCP) and United European Gastroenterology (UEG). Further, a guideline on mesh in pelvic colorectal surgery has been submitted to Colorectal Disease at the time of writing. New and updated guidelines should include patient representatives to further improve the relevance and likely uptake of their recommendations.

Better MDT working will help to support the more complex patients, particularly those with multi-compartment disease. The development of MDTs has led in some centres to joint clinics, which are essential to evaluate (in one consultation) the most complex patients. However, since these are a limited and expensive resource, local teams should develop clear vetting procedures and establish strict referral criteria for access to this high-resource clinic. Guidelines in general for MDT referral will be necessary to ensure that all MDTs do not discuss inappropriate cases.

MDTs should be conducted as frequently as required in order to reduce patient waiting times (Balachandran et al., 2015), and should be attended by subspecialist functional colorectal, urogynaecology and urology team members. Ideally, two members of each specialist team should be on the MDT group so that one can attend if the other is unavailable (Balachandran et al., 2015). Online meeting technology may allow for more cost- and time-efficient MDT meetings and allow specialists to join and leave as required (see Chapter B).

The knowledge and training of specialist nurses is valuable for joined-up pelvic floor care, and the continence resources available from the RCN (RCN, 2016) provide a comprehensive overview and support for patient-centred care. One-stop clinics and use of patient navigators, with or without administrators or triage nurses, can help to triage patients according to local guidelines and thereby streamline investigations – these investigations should ideally be conducted prior to clinician review in order to enhance decision making.

ADDITIONAL APPROACHES TO OPTIMISE MDT EFFICIENCY

An online questionnaire can be completed prior to remote MDT meetings, offering a standardised approach and a full picture of the patient’s issues, symptoms and goals: see Chapter B.

Making use of available skills: the case of protocol-driven procedures for nurses

With growing demands on the service, it is time to reconsider which procedures require consultant expertise and which can be performed by appropriately trained nursing or allied healthcare professionals such as Assistant Practitioners. Often acting as leaders in the area of bladder and bowel care, specialist nurses are uniquely placed to step into many procedures in this area. Provision of clear protocols and formal governance arrangements ensures that procedures are standardised, minimising risk to the patient and providing an opportunity for the healthcare practitioner to work towards independent practice. Indeed, many experienced nursing staff can use their expertise and clinical judgement, with the appropriate governance, to conduct procedures. For higher-cost procedures, such as sacral neuromodulation (SNM) implants, procedures can be performed along with a consultant, but with appropriate training procedures under local anaesthetic could also be performed independently, freeing up specialist consultants to perform other procedures.

As part of this approach, a national recruitment drive for specialist nurses is important to ensure sufficient manpower is available – this could ultimately bring about further cost savings.

CASE STUDY: NURSE-LED BOTULINUM TOXIN ADMINISTRATION

A nurse-led service administering botulinum toxin via flexible cystoscopy for overactive bladder the spinal injury setting was launched in 2016 (Muter P, SCI Nurse Conf 2016 – poster). Training was provided via a nationally agreed universal training package from the British Association of Urology Nurses (BAUN) and British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and a standard operating procedure ensured compliance and consistency in the process.

The outcome: waiting times were reduced and patients were highly satisfied with the service: 100% expressed confidence in their treating clinician (Muter P, SCI Nurse Conf 2018 – plenary presentation).

CASE STUDY: NURSE-LED SNM SERVICE

A nurse-led SNM service launched in 2017 has both reduced waiting times and ensured a consistent point of contact and treatment for patients (Mullins D, 2019). Further training was delivered by a Master’s Degree in surgical care practice in general surgery in order to set up the service.

The outcome: waiting times were reduced from 15 weeks to two weeks for test implants and nine for permanent implants; the majority of patients rated the service as outstanding. Consultant time and theatre availability were freed up, resulting in overall efficiency improvements.

The long-term view: training the pelvic floor workforce of the future

Currently there are around 100 unfilled urology posts in the UK, and the shortfall in pelvic floor expertise is expected to increase further. Specifically in surgery, there is a worrying trend of reduced applications for general surgery at Specialty Registrar level, as well as a paucity of people interested in taking up pelvic floor surgery: the recent negative media surrounding mesh may worsen this and create further issues in the future. Functional and incontinence work has always been something of a ‘Cinderella’ speciality, with cancer and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) work seen as more challenging and rewarding. However, an improved understanding of pelvic floor conditions has created a pivot point with the perception of this field. Nursing is also under pressure: the previous provision of specialist continence training under the old English National Board (ENB) structure no longer exists and specialist post-graduate continence training is lacking. This reduces the opportunity to specialise in this area of care for adults and for children, and also reduces the visibility of any such career path.

Defining the workforce required to provide evidence-based care is a further stated aim of the NBBH project (NHS Supply Chain). It is essential to attract new trainees to the service – and abandoning the past approach of considering the three pelvic compartments entirely separately may help to do this. With many trainees struggling to meet the required number of procedures to qualify in their chosen specialty, and a large number of senior surgeons now on the brink of retirement, creating a new combined specialty can help to both make the best use of our available resource and attract the pelvic floor specialists of the future.

Colorectal, urology and urogynaecology functional subspecialists all need to be adequately trained in their individual specialties, and then ensure they are able to tackle the often-complex problems encountered in each compartment of the pelvic floor. However, specialist training across the different compartments is a desirable long-term goal to reduce siloed decision making. Equal emphasis in such specialist training should be placed on each aspect of the pelvic floor, with the ultimate aim of creating ‘three-compartment pelvic floor specialists’. This may involve, for example, a urogynaecologist training in colorectal for a period, with similar cross-compartmental training for urologists and colorectal specialists. Cross-specialty pelvic floor training fellowships should be encouraged.

Training and education are crucial to improving the quality and availability of pelvic floor services. Future specialists, nurses and allied healthcare professionals need access to structured training programmes and specialist fellowships, as well as modular courses. The hub-and-spoke approach outlined in Chapter B should result in a higher concentration of cases and expertise, thereby maximising training opportunities.

FORTHCOMING PELVIC FLOOR GUIDELINES

NICE are developing a new guideline on the prevention and non-surgical management of pelvic floor dysfunction in women (including young women over the age of 12), which is due to be published in late 2021.

It aims to provide overarching guidance on pelvic floor dysfunction affecting all compartments of the pelvic floor and will include urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse as well as other symptoms attributed to pelvic floor dysfunction such as emptying disorders of the bowel and bladder, pain and dyspareunia

It is recognised that there is currently variation in the availability of and access to non-surgical management options, such as pelvic floor muscle training, for women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Women have no clear and effective strategies available to prevent worsening of the condition.

The guideline will focus on community-based pathways that include pelvic floor care and prevention of pelvic floor dysfunction. These pathways are intended to reduce the number of women who go on to develop complex symptoms that would need specialist care (e.g. surgery).

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10123/documents/final-scope

A further aspiration for the future could be a focus on ‘Pelvic Floor’ as a specialism rather than urology, urogynaecology and colorectal all being specialities in their own right (Beggs et al., 2014; Gash et al., 2015): this could help in recruiting and attracting talent to this speciality, securing a high quality of care for the future. Formal accreditation of units is currently offered by the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) and includes a requirement for provision of training, and the Pelvic Floor Society also offers accreditation to pelvic floor MDTs (see Chapter C), but a greater emphasis on training standards and broad curricula by professional organisations like the BSUG and British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) would be welcomed in order to help to build momentum for this cross-functional specialism.

Having nurses who can deliver treatment for both urinary and bowel symptoms, as already done by physiotherapists, could shorten the overall patient pathway and may allow some women to avoid surgery – for example, women with small posterior compartment prolapses and defaecatory symptoms who present to gynaecologists may be able to avoid surgery if they have access to appropriate conservative treatment. The protocol-driven procedures conducted by nurses, mentioned above, could also be performed across specialties where appropriate, to reduce duplication of effort and equipment and to maximise efficiencies. Specialist continence training, and a better-promoted career pathway, could also help to safeguard staffing levels in nursing for the future.

In the long run, guidelines should reflect this approach, providing guidance on an agreed, evidence-based national pathway for patients with complex pelvic floor disorders across the spectrum of disease. These guidelines would support primary care clinicians and specialists to ask all the right questions and conduct all appropriate investigations to ensure the best outcome for patients. The recent publication of the UK Clinical Guideline (POGP and UKCS, 2020) for best practice in the use of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse provides a good example where the patient’s needs are potentially met by a range of clinicians with appropriate and shared training as part of the overall management of their pelvic floor condition. It is encouraging that overarching NICE guidelines for pelvic floor disorders in women are anticipated in 2021 (see box on previous page). It is also important that sufficient workforce is available for the approaches outlined above to ensure that services are not unnecessarily centralised and the travel burden for patients is not excessively high.

REFERENCES

Balachandran A, Duckett J, 2015. What is the role of the multidisciplinary team in the management of urinary incontinence? Int Urogynaecol J 26:791–793.

Mullins D, 2019. Establishing a nurse-led sacral nerve stimulation service. Nurs Times 115;22–23.

Muter P, 2016. Nurse led flexible cystoscopy and injection of botulinum toxin A for patients within a UK spinal injuries outpatients setting. SCI Nurse Conference, poster.

Muter P, 2018. Nurse led Flexible Cystoscopy and Injection of Botulinum Toxin A for patients within Sheffield Spinal Injuries Outpatients Department. Patient satisfaction outcome. SCI Nurse Conference, plenary presentation.

NHS Supply Chain. National Bladder and Bowel Health Project. Available at: https://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/programmes/national-bladder-and-bowel-health-project/ (last accessed March 2021).

NICE guidelines, 2007. Faecal incontinence in adults: management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg49 (last accessed October 2020).

NICE guidelines, 2019. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123 (last accessed October 2020).

POGP, 2020. Membership Categories. Available at: https://thepogp.co.uk/membership/membership_categories.aspx (last accessed March 2021).

POGP and UKCS, 2020. UK Clinical Guideline for best practice in the use of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse. Available at: https://thepogp.co.uk/professionals/resources/pessariesforpros.aspx (last accessed April 2021).

Royal College of Nursing, 2016. Continence Resource. Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/continence (last accessed April 2021).

Salvador JC, et al., 2019. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of the female pelvic floor—a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 10:4.

Scottish Independent Review, 2017. Scottish Independent Review of the use, safety and efficacy of transvaginal mesh implants in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: Final Report. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-independent-review-use-safety-efficacy-transvaginal-mesh-implants-treatment-9781786528711/ (last accessed October 2020).